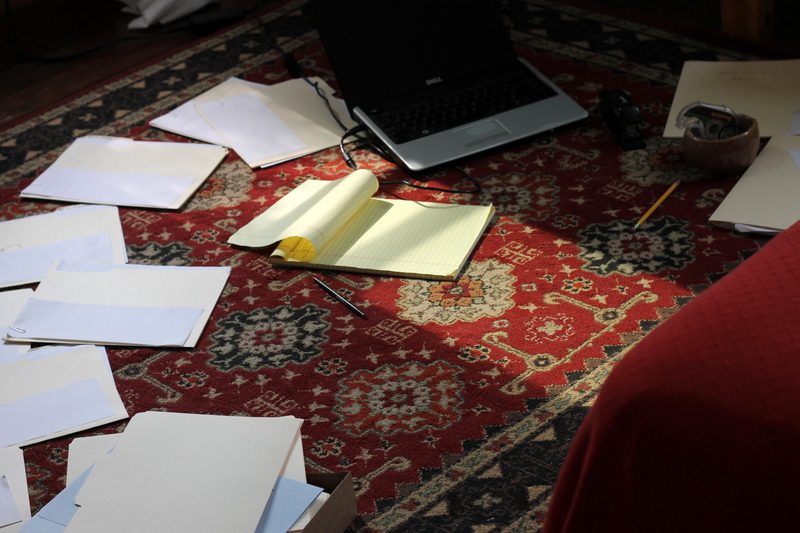

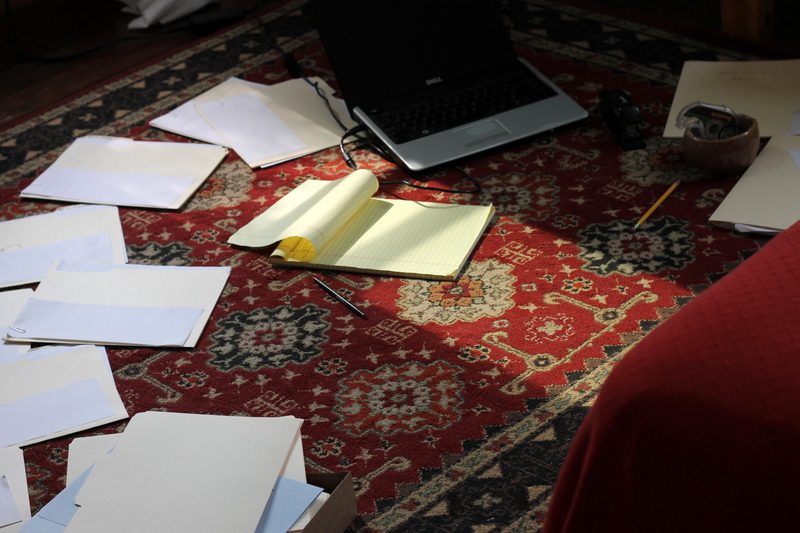

As you already know, I’m writing a book. This sounds much more straightforward and easy than it is.

Writing a book is actually more like deciding to enter a wicked-hard race even though you’ve never run a race before. But everyone tells you you can do it—No sweat, really, they shout cheerfully from their comfy easy chairs—and they keep insisting that you can absolutely do it, for crying out loud, until you actually start to believe them, partly because you think it might be fun to run a race and partly out of curiosity—could you actually do something that difficult?—and partly because you have a sneaking suspicion that you might be more amazing than you think.

So you take a couple deep bracing breaths, do some athletic-looking leg lunges, and start running. But something doesn’t feel right, and that’s when you look down and realize that you don’t have feet. Oh crap, no feet. So you start crawling—the race is happening, you can’t quit now—but the pavement hurts your knees and gravel gets stuck in the palms of your hands and you can’t really see where you’re going and that’s when it dawns on you that this is absolutely not invigorating. It’s demoralizing and utterly wretched and how long is this race supposed to be anyway? And what if you don’t actually have what it takes to run the race?

As you gimp along, half in the ditch, half out, ruing the stupid day you let your stupid ego talk you into this stupid race, a fancy electric car purrs by, followed by a ragey, big-ass pick-up truck and you choke on their dust and fumes and your eyes water and you start to wonder what’s the point of running anyway when there are so many faster ways to get somewhere. And that’s when you notice that there are no other runners in this race. It’s just you, by yourself, and suddenly you feel sad and pathetic but also just a teeny bit noble for doing something that no one else can see because maybe you are a little bit awesome anyway? Even if you don’t have feet?

And then you look behind you and see tracks. Not sneaker tracks, because obviously, but snakey tracks. They’re swervey and smooshy-looking and dishearteningly indecisive, but they’re yours and you’re like, Cool, I actually moved. And then you’re like, Well heck, inching along isn’t so bad as long as I can take however many breaks I need.

And then you notice that you smell honeysuckle and the breeze feels tingly-cool and that mist over yonder ridge—the ridge you can see when you peer under your left armpit (you’re crawling, remember)—is so ethereal that it almost convinces you that magic really does exist. And then you realize that as long as you don’t look straight ahead—and if you cover your eyes and hold your breath when the cars whiz by—this going-somewhere-slow-all-by-your-lonesome deal isn’t actually all that bad. Gives you something to do and all…

That’s what writing a book is like.

This same time, years previous: retreating, 2012 garden stats and notes, blasted cake, the best parts, whooooosh, lemon-butter pasta with spaghetti. on being green, hot chocolate, and Indian chicken.