Word on the street is that The Masses want to know how Our Work is going and What We Actually DO All Day.

Why, shop at the Walmart grocery store and go to the market! I thought I told you already!

(Kidding.)

Just the other day, my husband and I read over our job descriptions again. One phrase in particular caught my eye: of the ten qualifications for an MCC worker, the last one read, “Willingness to live simply.”

We both kinda snorted. “Living simply” is a nebulous and fraught phrase the world over, perhaps all the more charged when living (simply) in an impoverished culture.

“It should read “willingness to simply live,” I quipped, and only after I said it did I realize how true those words are.

Yes, we get Work done (on our better days), but much of what we do here, and much of what we did for our three years in Nicaragua, is simply live. (I can’t italicize that word enough. In developing countries, “living” takes on a weight that it doesn’t have in the States. I’m not glorifying it, and I’m not implying it’s worse—it’s just very, very different.)

We traipse through town and say Buenos dias to every Diego, Roberto, and Javier we pass. We squish into buses. We get ripped off in the market because we don’t know any better. We buy the wrong kind of ajax (“ah-hax”) for the house help because we can’t find it in the fancy grocery store. We experiment cooking with the fat purple beans that we find for sale along the road, the vendor squatted down by the basket, her snotty-nosed, ebullient little boy sifting through them like it’s his own private sandbox. We travel to other towns to make bank deposits. We wake our children at 5:45 every school-day morning and then deal with the fallout. We make connections and phone calls and purchases. We read maps and ask questions. We order (and finally get!) the kids’ long lists of school books. We get a call from our children’s school explaining that our little boy got into a pretend scuffle with another little boy, but then the other little boy, who just happens to know karate (at which point I interrupted the soft-spoken school director and with loud guffaws) got mad and punched our little boy in the face. Twice. (Our little boy didn’t even mention his purple face when he came home—I had to approach him to get the story.) Almost daily, we wash uniform shirts by hand (yes, even though we have a machine now) and hang them up to dry. We spend hours at the kids’ school enduring blasting loud music and watching a slew of talent shows that mostly involved dances based on this song. We pack lunches and make beds and clean and oversee (kinda) the pack of firecracker-loving boys. We read books and buy jugs of purified water and try to keep the dogs from attacking the taxi drivers that drop us off at our door. We argue and cry and tell jokes and problem solve and dole out consequences and laugh. We live.

See the purple spot? The picture doesn’t do it justice—there’s a strip of purple from the inside corner of his eye across to his cheekbone, and it’s swollen and glossy.

Quite dashing, no?

But this still doesn’t answer the question: what about work? Because really, that’s why we’re here, right? Right?

Our job descriptions were clear and succinct. Our actual jobs are not.

We fully expected this. Most MCC assignments are complex and complicated and a wee bit ornery. But so are we. It’s a good match.

At present, we’re taking it a week at a time. I mean this literally. Every Sunday, my husband and I look at the kids’ school calendars and our own calendar. We assess what needs to happen and how to go about getting it done. We divide up our hours at the school—who will be there when and for how long. And then every night we review the next day’s schedule—what needs to happen at school, what needs to happen at home, who will have time to buy the eggs on their mad dash from work to home in an attempt to get there before the kids do.

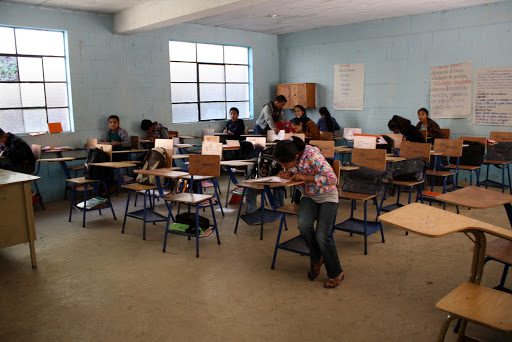

Currently, I’m teaching two English classes—4th and 5th grades (US 10th and 11th). (When I start two paragraphs in a row with words like “at present” and “currently,” it’s an indicator of how temporal our work really is!)

I love teaching, and I love the students. Some of them struggle with the basics, and some of them are whipsnap smart. I have zero discipline problems.

My default work involves hanging out in the library and in the teachers’ room, visiting, asking questions, and observing how the school is run.

Some days it’s excruciatingly boring, and other days it’s lots of fun.

The teachers are friendly, generous, and welcoming. One morning I took in a bag of hot biscuits and jam. In return (or maybe, just because), they tell me the best un-touristy vacation spots, how to cook the new-to-me vegetables, and laugh at all the dumb stuff I say.

I’ve been interviewing students, finding out their experiences at Bezaleel, and, in particular, in relation to MCC’s Saturday Vocational Arts program. The students love the final step of the interview process: getting their pictures taken.

I’m hoping to find ways to tutor some of the students who have a faulty educational background. Also, I’d like to start a mid-week baking class for the 4th grade girls.

My husband spends his days helping out the maintenance guys.

For a couple weeks, some masons were redoing the concrete court, so he helped with that.

He’s been making cake pans out of tin and wire for the baking class, and he wants to teach the students to make them themselves. These days, he’s been working at organizing and sorting the storage shed.

He’s hoping to teach carpentry to the 4th grade boys (for some undetermined reason, the entire 4th grade class is not participating in the vocational arts program), and to help build a carpentry workshop for the school while including the students in the process.

While we were originally sent to provide support to the Saturday Vocational Arts Program, we have not been able to find our niche in that particular area. They already have teachers and classes lined up, and it seems to be running smoothly, so my husband goes for part of the day while I usually stay home with the children who, by the end of the week, are in desperate need of an unstructured day.

There’s lots of work to be done at the school, but the way to accomplishing it isn’t very straightforward. Therefore, it’s kind of hard to talk about our work in terms that people back home will be able to relate to, and so I keep quiet. However, don’t equate my silence with lack of trying! We are constantly wrestling with the issues at Bezaleel, looking for ways to fit in and be helpful without taking over or bulldozing the local culture.

There. Are The Masses sufficiently placated?